Report: Virginia Students Deserve Fully-Trained Teachers

May 10, 2023

May 10, 2023

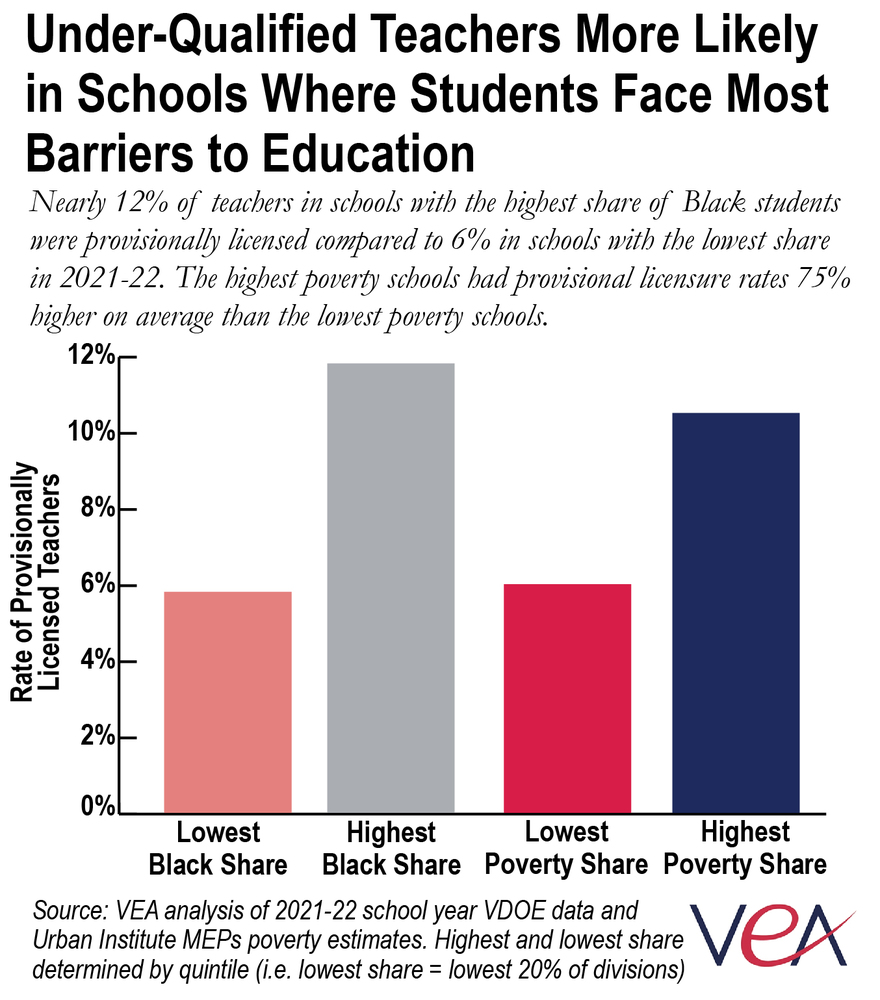

We all agree that Virginia’s students, no matter their ethnicity, family income status, or any other factor that makes them unique, deserve teachers who are qualified, prepared, and trained. Well-prepared teachers produce high-achieving students. Yet many students in our state are being taught by teachers with only a provisional license, which doesn’t require any completed teacher preparation coursework; and students of color and students living in households experiencing poverty are more likely to be taught by these underqualified teachers than students from higher-income and less diverse schools.

Rather than making meaningful investments in Virginia’s teachers to change this trend, our governor has instead chosen to address the teacher shortage by supporting a dramatic expansion in the number of provisionally licensed teachers. There are several avenues to address teacher shortages and teacher retention that do not further disadvantage children who already face the most barriers to learning.

Rather than making meaningful investments in Virginia’s teachers to change this trend, our governor has instead chosen to address the teacher shortage by supporting a dramatic expansion in the number of provisionally licensed teachers. There are several avenues to address teacher shortages and teacher retention that do not further disadvantage children who already face the most barriers to learning.

The teacher shortage in Virginia is real, with multiple causes. Despite Virginia being one of the top 10 states for household income, a 2022 Economic Policy Institute study showed the Commonwealth third-to-last in “teacher wage penalty” (the gap between teacher’s salaries and those of other similarly-educated professionals). The Covid pandemic has been especially hard on our nation’s teachers. A recent Gallup poll found that K-12 workers have the highest levels of burnout among all industries nationally. Teachers also deal with a lack of respect from legislators and the public. Because of these issues and others, more teachers are leaving the profession, and fewer students are entering teacher preparation programs.

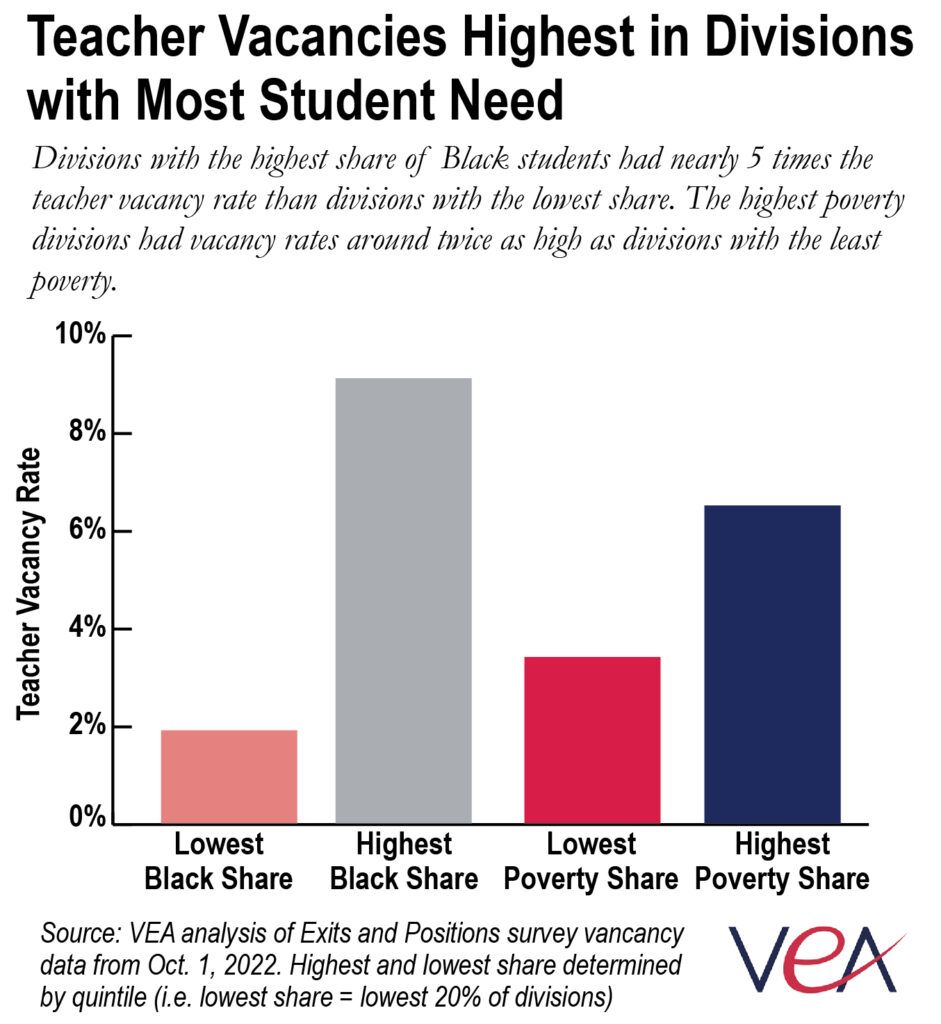

Analysis of Virginia Department of Education (VDOE) data shows that minority and low-income students are more likely to attend schools with a high teacher vacancy rate. Our analysis found that the teacher vacancy rate in schools with the highest share of students experiencing poverty (6.5%, top 20% of school divisions by poverty share) is nearly double the rate in lowest-share schools (3.4%). The vacancy rate in schools with the lowest share of Black students is 1.9%, while schools with the highest share have a vacancy rate of 9.1% — almost 5 times higher.

States across the country are scrambling to fill teacher vacancies, and Virginia is no different. School districts have tried solutions such as using long-term substitutes in place of teachers, increasing class sizes, using teachers trained in other subject areas to fill high-demand teaching slots, and hiring provisionally licensed teachers. Allowing under-prepared teachers to fill the gap may seem necessary in the short term, but it is not an acceptable long-term solution for Virginia’s students.

In an attempt to address Virginia’s teacher shortage crisis, Governor Youngkin issued Executive Directive Number Three last September, loosening requirements for teacher licensure, and encouraging “career switchers, military veterans and other professionals” to try their hand at teaching. Prior to the signing of this directive, the percentage of Virginia’s teachers who were provisionally licensed was 7.7%. In the highest-poverty schools, the rate was 10.5%, and in schools with the highest share of Black students the rate was 11.8%. With the governor actively promoting loosened teacher licensing requirements, we can expect these percentages to increase.

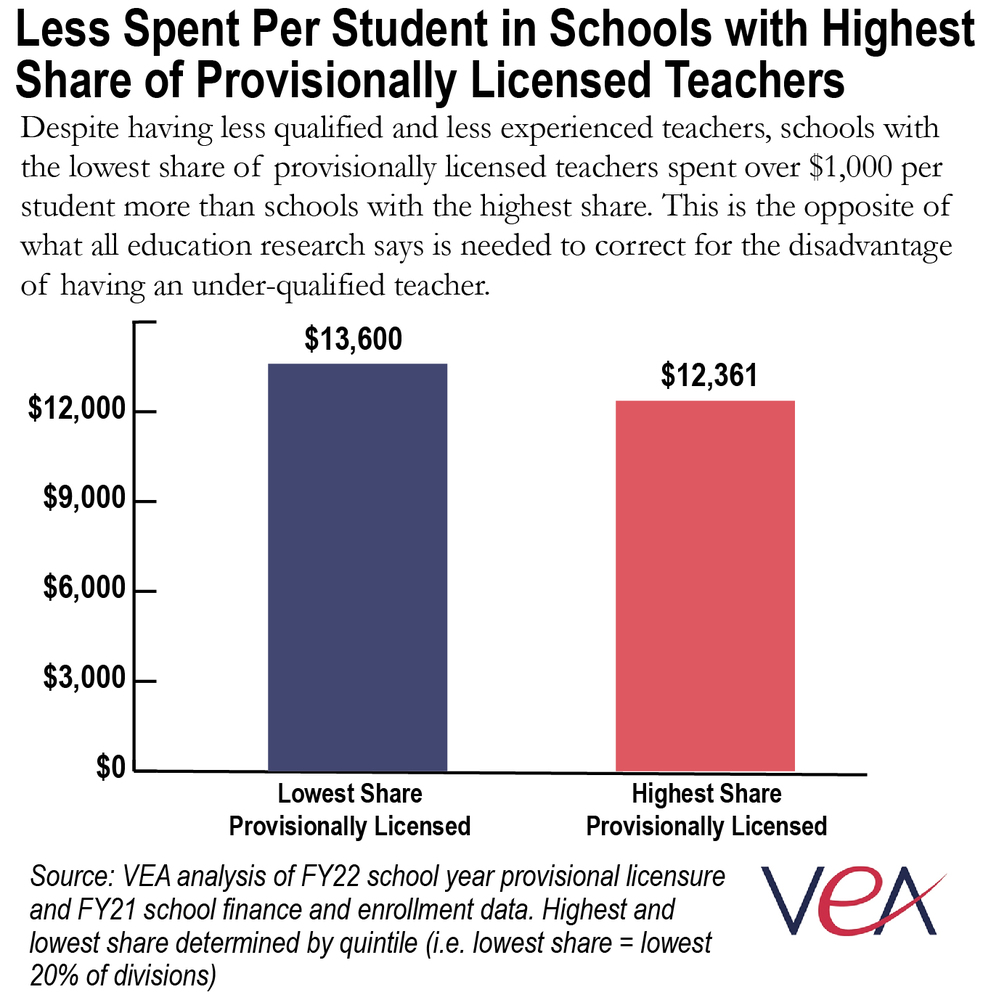

VEA’s analysis of 2021-22 VDOE data further shows that schools with the highest share of provisionally licensed teachers spend the least amount per student ($12,361, compared to $13,600 in schools with the lowest share). Where a student lives in the state has a determining impact on their chances of having a provisionally licensed teacher. Children in schools in the Southwest and the Valley are almost half as likely to have a provisionally licensed teacher as are students in Southside and the Northern Neck.

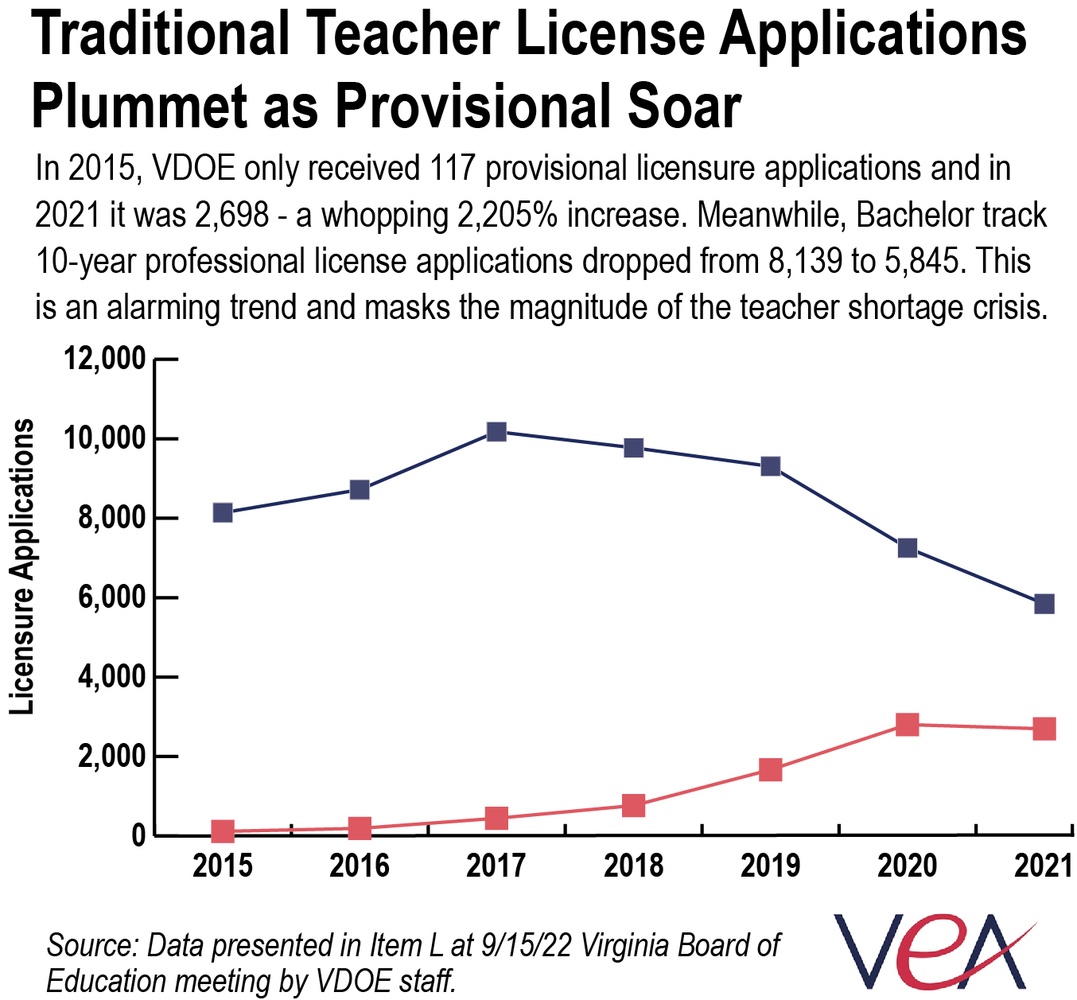

The number of applications for provisional licenses in Virginia has grown exponentially, from 117 in 2015 to 2,698 in 2021—a more than 2000% increase. With the governor’s executive directive now in play, we can expect the number of provisional license applications to continue increasing.

In Virginia, provisionally licensed teachers have a dropout rate of 18% by the end of the third year of teaching, more than 60% higher than traditionally licensed teachers. Instead of providing what amounts to on-the-job training for underqualified prospective teachers, who are significantly more likely to leave, we should be focusing our efforts on solutions that have been shown to work. A 2022 working paper from Brown University found that teacher shortages and the employment of underqualified teachers tend to be higher in low-spending states. Virginia is a top-10 state in household income, but ranks 40th in per-pupil state funding, according to the most recent Census figures. In 2022, Business.org ranked states by average teacher salary when compared with salaries for all jobs in the state — Virginia was ranked 49th. Increasing our investment in education will pay off both in attracting new well-trained teachers, as well as in retaining existing teachers.

Solutions to Address the Root of the Problem

#1 It is clear that Virginia must start with providing competitive teacher pay at all levels if we want to change the trend of qualified teachers leaving the field and provisionally licensed teachers taking their place. While this may be the most essential step, there are several other systemic and targeted approaches lawmakers in Virginia can take to meaningfully address the challenge.

#2 In a recent study out of Dallas, it was found that providing additional financial incentives in the $6,000-$10,000 range to attract high performing teachers to the lowest achieving schools resulted in substantial improvements in students’ math and reading scores, and also improved teacher retention. We know from the data analysis presented above that vacancy rates and provisionally licensed teacher percentages are highest in schools with the most poverty and racial diversity in Virginia. Targeted state supplemental payments to teachers working in high-poverty and -need schools would be an effective strategy to attract and retain skilled educators.

#3 Another way to drive teacher retention and abate the teacher shortage is to lift the “support cap.” For years, this has limited state funding for essential support staff positions in schools. Providing school divisions with this additional funding would free up local funds for more competitive teacher salaries. Additional school personnel would also mean teachers wouldn’t have to wear so many hats – serving the roles of counselor, nurse, custodian and attendance clerk – and could instead focus more on their speciality: instruction. With tens of thousands more students than when the support cap was put in place, and thousands less support staff in our schools, there is more pressure than ever on the remaining staff to plug the gaps.

#4 Raising the state’s targeted supplemental payment to high-poverty schools, known as the At-Risk Add On, would also provide critical funding to divisions with high concentrations of students who face significant barriers to education. The variation in localities’ ability to raise revenue leads to differing educational experiences across the state, with students from areas with high concentrations of poverty receiving inadequate support and having fewer opportunities than those in wealthier areas, who tend to have newer textbooks, more electives, newer technology, fewer staff vacancies, and smaller class sizes. Studies show that students facing more barriers and those living in poverty generally need an additional funding supplement of 40-200% in order to have education outcomes comparable to students not living in poverty. Increasing the At-Risk Add-On funding would provide flexible support for schools to invest in essential services, such as supplemental pay to attract and retain skilled educators, particularly for student groups that have traditionally been underserved (minority students, students in homes experiencing poverty and housing instability, students in rural settings, and students learning English). With a low likelihood of any near-term updates to Virginia’s core K-12 funding formula, which hasn’t been revamped in decades, greatly scaling the At-Risk Add-On is the best prospect to adequately account for student need in state funding.

The solution to Virginia’s teacher shortage is not to seek out underqualified and under-trained individuals, hoping that they will one day become exceptional teachers. We must instead attack the problem at its root: retain the exceptional teachers we already have—by treating them with respect and appreciation–and pay them accordingly. Giving existing teachers respect, autonomy, and the pay they deserve will in turn motivate the students of today to view teaching as a valued and viable profession, thereby producing the exceptional teachers of tomorrow.

Note: Divisions/schools defined as having top or lowest shares of types of students are broken up by quintile (i.e., divisions with the highest share of Black students means the top 20% of divisions with the highest share)

Virginia is a top 10 state in median household income, but ranks 36th in the US in state per pupil funding of K-12 education.

Learn More